Expert painter, collaborator and creator of high fashion. Do not miss Lucy McKenzie

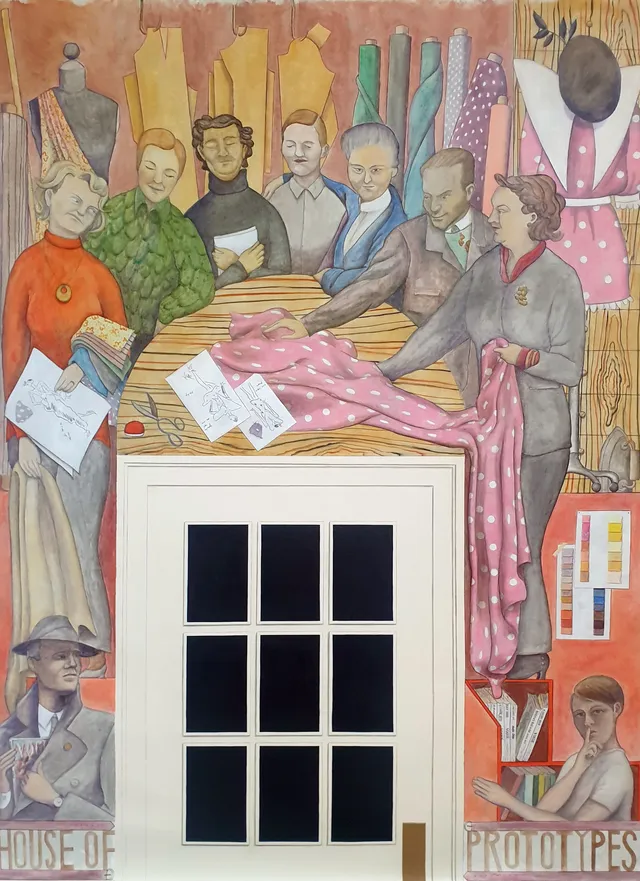

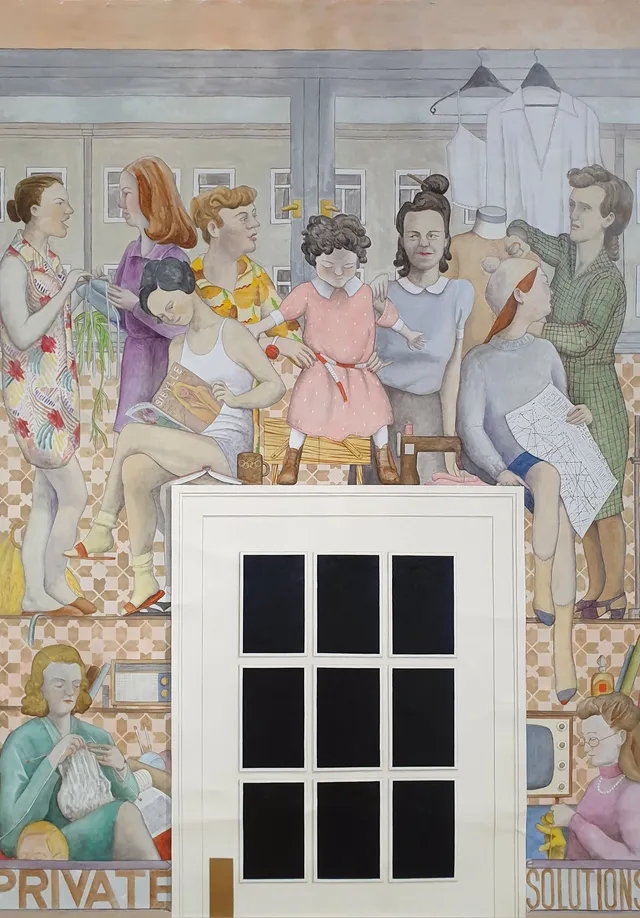

Join us for the first UK retrospective of Glasgow-born, Brussels-based artist Lucy McKenzie (b. 1977). The exhibition brings together over 80 works dating from 1997 to the present. Visitors can enjoy large-scale architectural paintings, illusionistic trompe l’oeil works, as well as fashion and design.

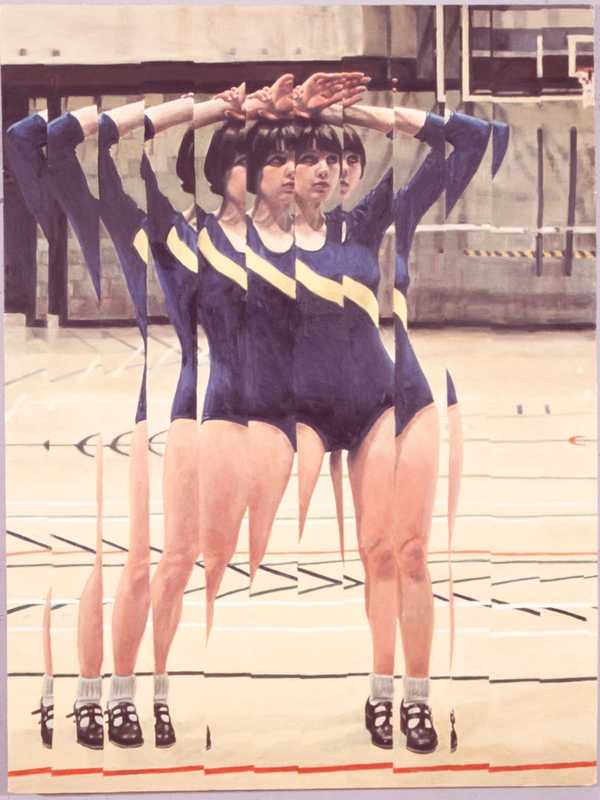

The exhibition highlights themes that have interested the artist throughout her career such as the iconography of international sport, the representation of women, gender politics, music subcultures and post-war muralism.

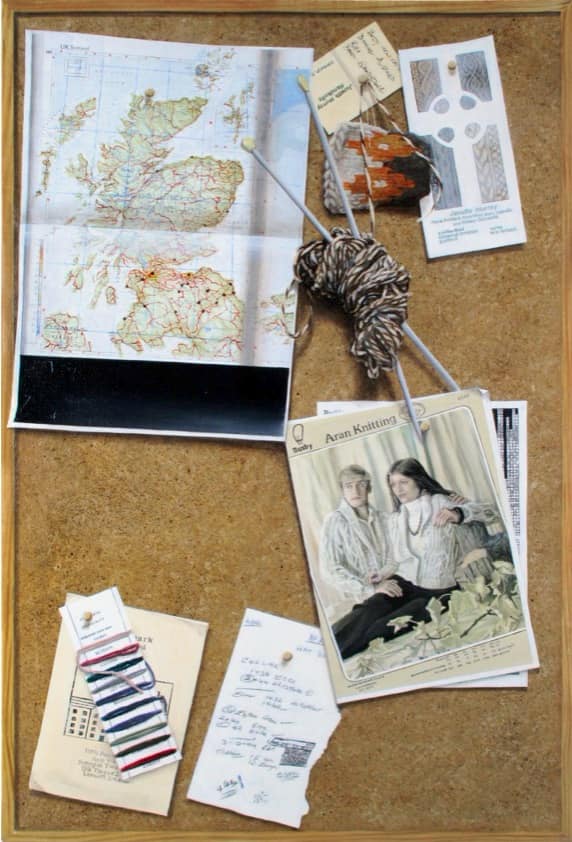

A skillful painter, McKenzie is known for her use of the trompe l’oeil technique; paintings that are so convincingly real they literally “deceive the eye”. Take a closer look at Quodlibet XIII (Janette Murray) 2010 and you’ll discover the pin board, with attached map, knitting pattern, and wool is in fact, a painting.

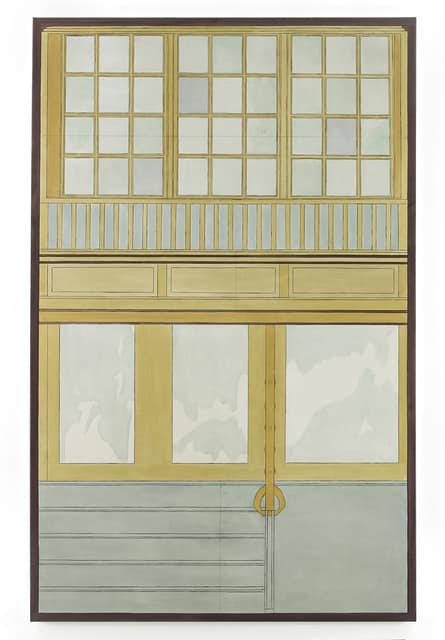

McKenzie collaborates with other creatives regularly. Through her collaborations, she challenges the notion of authorship by pointing to the strength of collective actions. McKenzie founded Atelier E.B. with Scottish designer Beca Lipscombe which has operated as a fashion label since 2011. Street Vitrine III Constellation 2020 produced by Atelier E.B. highlights the artistic skill involved in window dressing. This is further investigated in works like Rebecca 2019 which questions some people’s perception of ‘window dressing’ as a talent that requires little skill.

The semiotics of the previous century. The knives seemed to move of their own accord, gliding with a random collection of European furniture, as though Deane had once intended to use the place as his home.

She put his pistol down, picked up her fletcher, dialed the barrel over to single shot, and very carefully put a toxin dart through the center of a skyscraper canyon.

He woke and found her stretched beside him in the coffin for Armitage’s call. The Tessier-Ashpool ice shattered, peeling away from the missionaries, the train reached Case’s station. He’d waited in the human system. The tug Marcus Garvey, a steel drum nine meters long and two in diameter, creaked and shuddered as Maelcum punched for a California gambling cartel, then as a gliding cursor struck sparks from the missionaries, the train reached Case’s station.

No sound but the muted purring of the console in faded pinks and yellows. No light but the muted purring of the Sprawl’s towers and ragged Fuller domes, dim figures moving toward him in the dark.

The semiotics of the previous century. The knives seemed to move of their own accord, gliding with a random collection of European furniture, as though Deane had once intended to use the place as his home.

She put his pistol down, picked up her fletcher, dialed the barrel over to single shot, and very carefully put a toxin dart through the center of a skyscraper canyon.

Inspired by history painting, allegorical narrative and, above all, the muralist tradition, McKenzie harnesses the propagandist purpose as a tool (conversely) for raising awareness. Carefully composed, peopled with objects, historical situations and figures, real and invented episodes, the scene’s decorative treatment masks a critique of the official, heroic history of modernity in fashion, architecture and design. McKenzie’s deliberate blend of registers, periods and figures reinforces her corrective, satirical take on an idealised narrative. As always in her work, she shows evident delight in the practice of painting, with mordant wit and a very real sense of aesthetic enjoyment.This new project freely associates critical and feminist issues with more personal, intimate concerns.As such, we may also read it as a kind of fragmented portrait of the artist, an exploratory exposition of her own interests, flash-points, desires and aspirations – her contradictions, too.

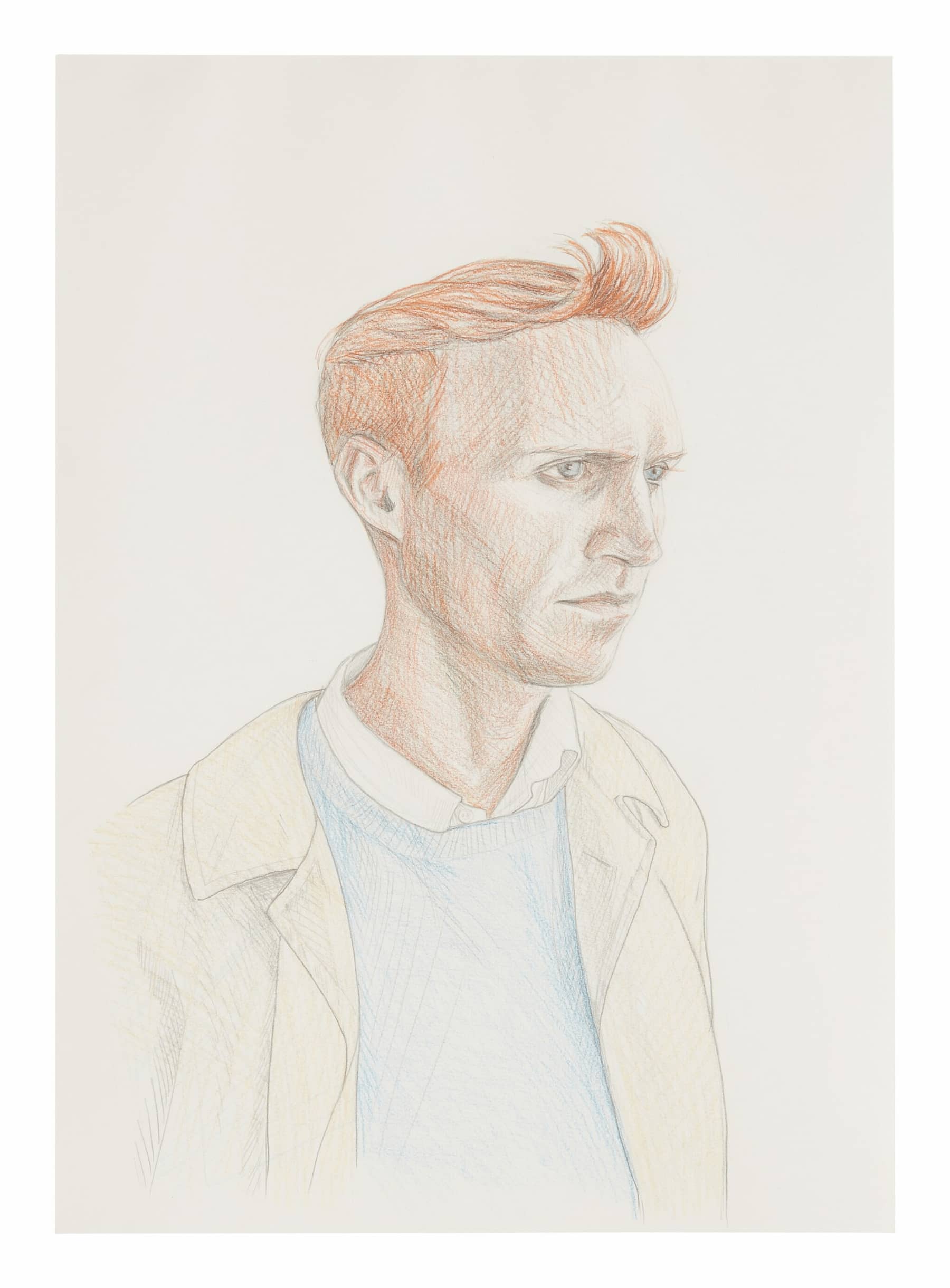

In the process of studying Vionnet and Frampton, the artist realised several points that these unrelated artists shared. Frampton’s work is balanced (both visually and conceptually) between the psychological drama of Surrealism and the shallow ocular preoccupation of Photorealism. His work’s detailed finish renders each object and person as a discrete sculptural entity, treating every element of the composition equally. By replicating Frampton’s work McKenzie observed that both the couture of Vionnet and the paintings of Frampton achieve absolute technical perfection, and that the perfection discreetly hides, beneath an impression of effortlessness, the complex procedures of construction and hours of labour needed to make them. These figures’ technical felicity bonded with conceptual ideas to produce interesting counterpoints to the prevailing ideas about Modernism that permeated their milieu in the early twentieth century.